Master design pattern OOP with our guide. Learn creational, structural, and behavioral patterns with clear, practical code examples to elevate your skills.

December 20, 2025 (2mo ago)

A Practical Guide to Design Pattern OOP

Master design pattern OOP with our guide. Learn creational, structural, and behavioral patterns with clear, practical code examples to elevate your skills.

← Back to blog

A Practical Guide to Design Pattern OOP

Master design pattern OOP with our guide. Learn creational, structural, and behavioral patterns with clear, practical code examples to elevate your skills.

Introduction

Design patterns in object-oriented programming are proven, reusable blueprints for solving recurring design challenges. They aren’t copy-and-paste code; they’re adaptable templates that help you structure classes and objects so your code is easier to maintain, extend, and test.

A solid grasp of common patterns—creational, structural, and behavioral—lets you communicate design intent clearly with teammates, refactor legacy code safely, and choose the right tool for each architectural problem.

What Are Design Patterns In Object Oriented Programming

Ever tried building something complex without a plan? Coding without design patterns can lead to a tangled codebase that’s hard to scale and maintain. Design patterns are like a master chef’s cookbook: tested recipes you adapt to produce consistent, maintainable results.

The Shared Language of Developers

One of the most valuable benefits of patterns is a shared vocabulary. Say “Factory” or “Singleton” and experienced developers immediately understand the intent and high-level structure, which speeds collaboration and architectural decisions.

“Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software,” published in 1994 by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides, catalogued 23 foundational patterns that remain essential reading for OOP practitioners2. These patterns build on earlier academic work showing measurable productivity and reuse benefits in large projects1.

A design pattern is not a finished design that can be transformed directly into code. It is a description or template for how to solve a problem that can be used in many different situations.

Getting comfortable with core OOP principles like polymorphism and inheritance helps you apply patterns effectively. For a practical refresher, see our guide comparing polymorphism vs inheritance.

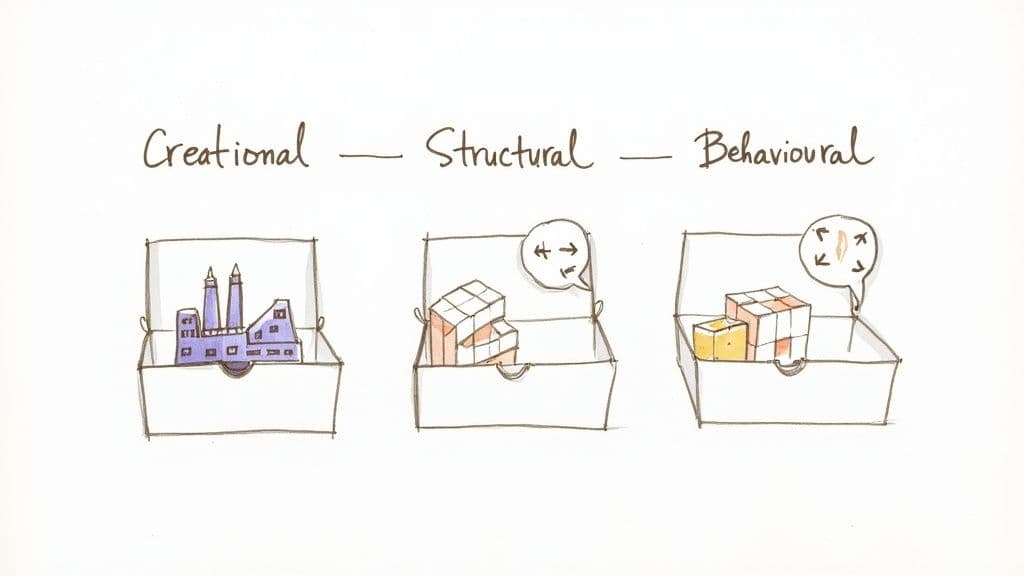

The Three Core Categories Of Design Patterns

The Gang of Four organized patterns into three categories: creational, structural, and behavioral. Knowing these categories helps you quickly pick the right approach for a problem.

Overview Of OOP Design Pattern Categories

| Pattern Category | Core Purpose | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Creational | Managing and abstracting object creation | Factory, Builder, Singleton, Prototype |

| Structural | Composing classes and objects into larger, flexible structures | Adapter, Decorator, Facade, Composite |

| Behavioral | Defining how objects interact and communicate | Observer, Strategy, Command, Iterator |

Creational Patterns: The Construction Specialists

Creational patterns control how objects are created so client code isn’t tightly coupled to concrete classes. They hide creation logic, increase flexibility, and let you manage instantiation (for instance, enforcing a single instance with Singleton).

Structural Patterns: The Architectural Glue

Structural patterns help you assemble objects into larger systems. They simplify relationships between components so you can change parts without breaking the whole system. Patterns like Adapter let incompatible interfaces cooperate, which is invaluable when integrating third-party libraries.

Structural patterns simplify system design by identifying simple ways to realize relationships between entities.

Behavioral Patterns: The Communication Directors

Behavioral patterns govern object interaction and responsibility. They create clean communication channels—Observer for event-driven notifications and Strategy for swapping algorithms without modifying clients.

By managing communication paths carefully, you reduce dependencies and make the codebase easier to reason about and maintain.

Creating Objects With Creational Patterns

Creational patterns introduce an abstraction layer around object creation, so you can swap implementations without changing client code. Below are two practical TypeScript examples: Singleton and Factory Method.

The Singleton Pattern: Ensuring One True Instance

Singleton ensures a class has only one instance and provides a global access point. It’s useful for shared resources like a database connection or logger, but it can introduce global state that complicates testing and dependency management3.

Example: a TypeScript Singleton for a database connection.

class DatabaseConnection {

private static instance: DatabaseConnection;

private constructor() {

// A private constructor prevents external 'new' calls

console.log("Connecting to the database...");

}

public static getInstance(): DatabaseConnection {

if (!DatabaseConnection.instance) {

DatabaseConnection.instance = new DatabaseConnection();

}

return DatabaseConnection.instance;

}

public query(sql: string): void {

console.log(`Executing query: ${sql}`);

}

}

// Usage

const db1 = DatabaseConnection.getInstance();

const db2 = DatabaseConnection.getInstance();

db1.query("SELECT * FROM users");

console.log(db1 === db2); // true

The Singleton trade-off: use Singletons for truly global resources, and prefer dependency injection for better testability and modularity3.

The Factory Method: Letting Subclasses Decide What to Create

Factory Method defines an interface for creating an object, while subclasses decide which concrete product to instantiate. It decouples client code from concrete classes, making the system easier to extend.

Example: rendering OS-specific buttons in TypeScript.

interface Button {

render(): void;

onClick(f: () => void): void;

}

class WindowsButton implements Button {

render() { console.log("Rendering a button in Windows style."); }

onClick(f: () => void) { console.log("Windows button click event."); f(); }

}

class MacButton implements Button {

render() { console.log("Rendering a button in macOS style."); }

onClick(f: () => void) { console.log("Mac button click event."); f(); }

}

abstract class Dialog {

abstract createButton(): Button;

render() {

const okButton = this.createButton();

okButton.render();

}

}

class WindowsDialog extends Dialog {

createButton(): Button { return new WindowsButton(); }

}

class MacDialog extends Dialog {

createButton(): Button { return new MacButton(); }

}

// Client

const os: string = "windows";

let dialog: Dialog;

if (os === "windows") dialog = new WindowsDialog(); else dialog = new MacDialog();

dialog.render();

Factory Method keeps the creator unaware of concrete products, making additions like a LinuxDialog straightforward.

Building Flexible Systems With Structural Patterns

Structural patterns help you compose objects into robust, adaptable systems. Two practical choices are Adapter and Decorator.

The Adapter Pattern: Bridging Incompatible Interfaces

Adapter wraps an incompatible interface so it conforms to what your system expects. This avoids invasive changes to legacy code.

Example: adapting a ModernLogger to an existing ILogger interface.

class ModernLogger {

public logInfo(message: string): void {

console.log(`[INFO]: ${message}`);

}

}

interface ILogger { log(message: string): void; }

class LoggerAdapter implements ILogger {

private modernLogger: ModernLogger;

constructor() { this.modernLogger = new ModernLogger(); }

public log(message: string): void { this.modernLogger.logInfo(message); }

}

const logger: ILogger = new LoggerAdapter();

logger.log("User logged in successfully.");

The Decorator Pattern: Adding Functionality Dynamically

Decorator adds responsibilities to objects at runtime by wrapping them. It’s more flexible than subclassing and follows the Single Responsibility Principle.

Example: composing a subscription with optional add-ons.

interface Subscription { getDescription(): string; getCost(): number; }

class BasicSubscription implements Subscription {

getDescription(): string { return "Basic Plan"; }

getCost(): number { return 10; }

}

abstract class SubscriptionDecorator implements Subscription {

protected subscription: Subscription;

constructor(subscription: Subscription) { this.subscription = subscription; }

abstract getDescription(): string;

abstract getCost(): number;

}

class PremiumSupportDecorator extends SubscriptionDecorator {

getDescription(): string { return `${this.subscription.getDescription()}, Premium Support`; }

getCost(): number { return this.subscription.getCost() + 5; }

}

class CloudStorageDecorator extends SubscriptionDecorator {

getDescription(): string { return `${this.subscription.getDescription()}, 1TB Cloud Storage`; }

getCost(): number { return this.subscription.getCost() + 7; }

}

let mySubscription: Subscription = new BasicSubscription();

mySubscription = new PremiumSupportDecorator(mySubscription);

mySubscription = new CloudStorageDecorator(mySubscription);

console.log(mySubscription.getDescription());

console.log(mySubscription.getCost());

This compositional approach keeps features modular and easy to test.

Managing Interactions With Behavioural Patterns

Behavioral patterns organize object communication so systems remain flexible and maintainable. Two core examples are Observer and Strategy.

The Observer Pattern: Notifying Interested Parties

Observer sets up a one-to-many relationship so that when a Subject changes state, Observers are notified automatically. It’s ideal for event-driven systems.

Example: a simple notification service.

interface Subject { attach(observer: Observer): void; detach(observer: Observer): void; notify(): void; }

interface Observer { update(subject: Subject): void; }

class NotificationService implements Subject {

public state: string = '';

private observers: Observer[] = [];

attach(observer: Observer): void { this.observers.push(observer); }

detach(observer: Observer): void { const i = this.observers.indexOf(observer); if (i !== -1) this.observers.splice(i, 1); }

notify(): void { for (const o of this.observers) o.update(this); }

public createNewPost(title: string): void { this.state = `New Post: ${title}`; console.log(`\nNotificationService: A new post was created.`); this.notify(); }

}

class EmailNotifier implements Observer { public update(subject: Subject): void { if (subject instanceof NotificationService) console.log(`EmailNotifier: Sending email about "${subject.state}"`); } }

class PushNotifier implements Observer { public update(subject: Subject): void { if (subject instanceof NotificationService) console.log(`PushNotifier: Sending push notification for "${subject.state}"`); } }

const notificationService = new NotificationService();

const emailer = new EmailNotifier();

const pusher = new PushNotifier();

notificationService.attach(emailer);

notificationService.attach(pusher);

notificationService.createNewPost("Understanding Observer Pattern");

notificationService.detach(pusher);

notificationService.createNewPost("Why Strategy is Awesome");

Observer produces a loosely coupled design: Subjects don’t need to know the concrete Observers they notify.

The Strategy Pattern: Encapsulating Algorithms

Strategy lets you swap algorithms at runtime, avoiding large conditional blocks. It aligns with the Open/Closed Principle by allowing new strategies without modifying existing code.4

Example: payment strategies for a shopping cart.

interface PaymentStrategy { pay(amount: number): void; }

class CreditCardStrategy implements PaymentStrategy { pay(amount: number): void { console.log(`Paying $${amount} with Credit Card.`); } }

class PayPalStrategy implements PaymentStrategy { pay(amount: number): void { console.log(`Paying $${amount} via PayPal.`); } }

class ShoppingCart {

private paymentStrategy: PaymentStrategy;

constructor(strategy: PaymentStrategy) { this.paymentStrategy = strategy; }

public setPaymentStrategy(strategy: PaymentStrategy) { this.paymentStrategy = strategy; }

public checkout(amount: number): void { this.paymentStrategy.pay(amount); }

}

const cart = new ShoppingCart(new CreditCardStrategy());

cart.checkout(150);

cart.setPaymentStrategy(new PayPalStrategy());

cart.checkout(150);

Strategy removes conditional complexity and makes systems easier to extend.

Common Design Pitfalls and Refactoring Strategies

Choosing a pattern is only half the battle. Avoid anti-patterns like the God Object, which hoards responsibilities and violates the Single Responsibility Principle. Look for code smells—long methods, excessive dependencies, or monster classes—and address them with disciplined refactoring.

Refactoring is about improving internal structure without changing external behavior. It’s how you tame legacy systems safely.

Refactoring to the Strategy Pattern

A large switch or long if/else chain is a classic smell. Refactor by extracting the varying behavior into a Strategy interface with concrete strategy classes. Replace the conditional with a single call to the selected strategy’s method. This change improves extensibility, testability, and alignment with SOLID principles4.

Answering Your Questions About OOP Design Patterns

How many design patterns should I learn?

Focus on 5–7 essential patterns first: Singleton, Factory, Adapter, Decorator, Observer, and Strategy. Learn the problem each pattern solves; once you internalize that, learning additional patterns becomes much easier.

When should I avoid using a design pattern?

Avoid patterns that add complexity without solving a real issue. Don’t introduce a pattern “just in case.” Follow YAGNI: add patterns when a clear, present problem warrants them.

Can I use design patterns with functional programming?

Yes. Many patterns map naturally to functional techniques. Strategy can be function parameters, and Decorator can be higher-order functions. The key is applying the underlying principle rather than rigidly copying OOP forms.

At Clean Code Guy, we help teams build software that lasts by embedding foundational principles into their workflow. Discover how our code audits and AI-ready refactoring can get your team shipping with confidence at https://cleancodeguy.com.

AI writes code.You make it last.

In the age of AI acceleration, clean code isn’t just good practice — it’s the difference between systems that scale and codebases that collapse under their own weight.