A practical guide to Robert Martin Clean Architecture. Learn its layers, principles, and real-world implementation for building scalable software.

November 30, 2025 (2mo ago)

Mastering Robert Martin Clean Architecture

A practical guide to Robert Martin Clean Architecture. Learn its layers, principles, and real-world implementation for building scalable software.

← Back to blog

Clean Architecture Guide — Robert C. Martin

Summary: Practical guide to Robert C. Martin’s Clean Architecture: layers, principles, TypeScript example, trade-offs, and implementation tips for scalable, testable systems.

Introduction

Robert C. Martin’s Clean Architecture puts your business logic at the centre of your system so it’s protected from changes in frameworks, databases, and UIs. This practical guide explains the layers, the Dependency Rule, real-world trade-offs, and a TypeScript/Node.js implementation for a simple “create user” feature.

What Is Clean Architecture?

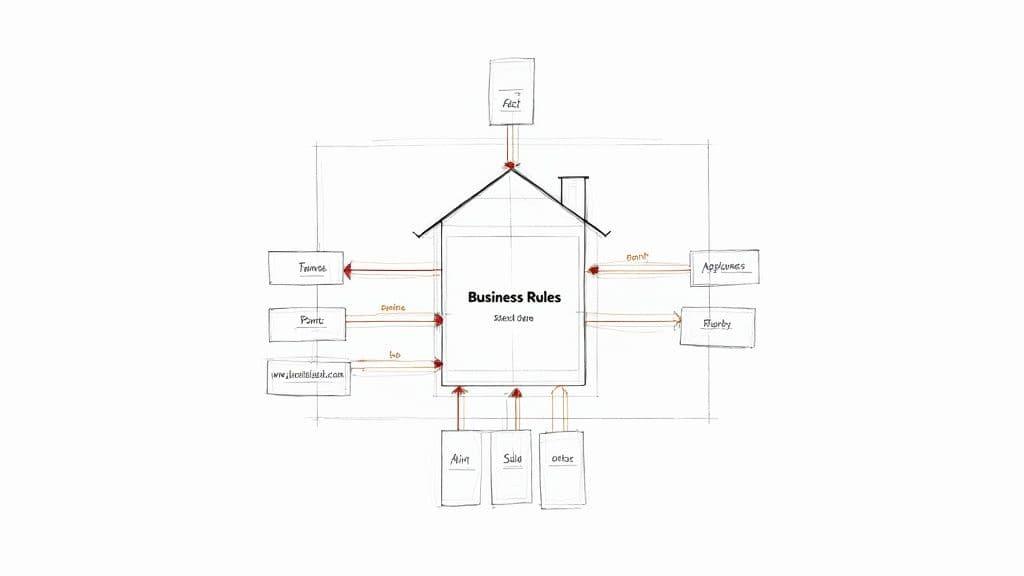

Many projects end up with business logic tangled with frameworks and databases, which makes changes risky and expensive. Clean Architecture enforces a strict separation of concerns through concentric layers so the code that makes your application unique—the business rules—doesn’t depend on delivery or infrastructure details.

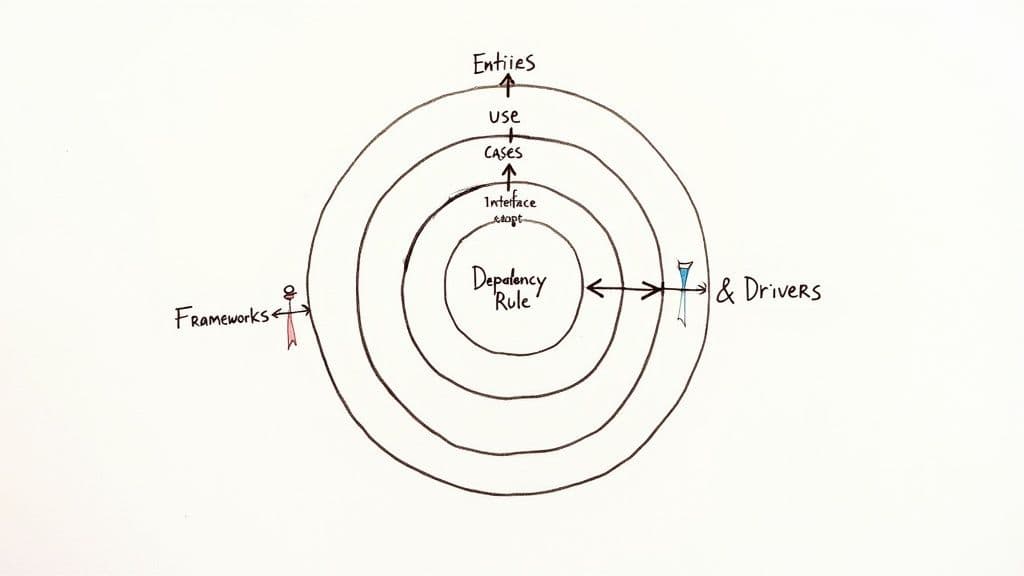

The model is governed by one core constraint: the Dependency Rule—source code dependencies must point inwards. This simple constraint unlocks practical benefits like framework independence, testability, database independence, and UI flexibility.

The Power of Independence

Because inner layers don’t know about outer layers, you can:

- Swap web frameworks without touching business logic.

- Run fast, isolated unit tests that don’t require a database or server.2

- Move between SQL and NoSQL storage with minimal core changes.

- Reuse the same core logic for a web app, mobile app, or CLI.

These advantages give your application the options to evolve rather than forcing early, irreversible decisions.

Core Goals of Clean Architecture

| Goal | Description | Business Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Independence | Decouple core logic from frameworks, UI, and databases. | Reduces vendor lock‑in and supports future technology changes. |

| Testability | Let business rules be tested in isolation. | Faster feedback and higher confidence in releases.2 |

| Maintainability | Keep changes localized and safer. | Lower long‑term cost of ownership and faster onboarding. |

| Scalability | Separate concerns so components can evolve independently. | Easier to scale parts of the system as load or complexity grows. |

These goals work together to make systems resilient and easier to evolve.

Standing on the Shoulders of Giants

Robert C. Martin popularized this unified model by synthesizing earlier patterns like Hexagonal (Ports and Adapters) and Onion Architecture; his book and talks helped make the diagram and vocabulary common in modern systems design.14

We apply these ideas in production systems and reference materials, for example the Clean Architecture PDF and other guides hosted on our site and blog pages (see internal resources: Clean Architecture PDF).

Understanding the Layers (Onion Model)

The architecture uses a concentric model. All dependencies point inward. Outer layers know about inner layers; inner layers know nothing about outer layers.

Layer 1: Entities — Core Business Logic

Entities are pure business objects that contain enterprise-wide rules. For an e-commerce system, an Order entity would calculate totals and validate shipping constraints. Entities should be stable and free of framework or persistence concerns.

Layer 2: Use Cases — Application Rules

Use Cases (Interactors) orchestrate Entities to achieve application-specific goals, such as “Create a User” or “Process a Payment.” They define inputs and outputs and should remain ignorant of delivery mechanisms.

Key point: Entities express enterprise rules; Use Cases express application behavior.

Layer 3: Interface Adapters — Translators

This layer contains controllers, presenters, and repository interfaces that translate data between the outer infrastructure and the inner application. Repositories are defined as interfaces (ports) that Use Cases depend on; concrete adapters live outside the core.

Layer 4: Frameworks & Drivers — Outermost Details

Outermost code is framework and infrastructure glue: web frameworks, databases, UI frameworks, third‑party libraries. This layer is expected to be volatile; placing it outside the core minimizes the blast radius of changes.

Building a Service with TypeScript and Node.js

Below is a practical walkthrough for a “create user” feature showing how to map the onion layers to a real project.

Project Folder Structure

A folder structure that mirrors the layers helps enforce boundaries:

- src/

- domain/: Entities

- application/: Use Cases and ports

- infrastructure/: Database connections, adapters

- interfaces/: Controllers, route handlers

Step 1: Defining the User Entity

// src/domain/user.ts

export class User {

constructor(

public readonly id: string,

public name: string,

public email: string,

private createdAt: Date,

) {}

public static create(id: string, name: string, email: string): User {

if (!name || name.length < 2) {

throw new Error(“User name must be at least 2 characters long.”);

}

return new User(id, name, email, new Date());

}

}

This entity contains only business rules and no persistence or framework details.

Step 2: Creating the Use Case

Define a repository interface as a port so the use case depends on an abstraction, not a concrete implementation.

// src/application/ports/userRepository.ts

import { User } from '../../domain/user';

export interface UserRepository {

save(user: User): Promise<void>;

findByEmail(email: string): Promise<User | null>;

}

Now the use case:

// src/application/createUserUseCase.ts

import { User } from '../domain/user';

import { UserRepository } from './ports/userRepository';

export class CreateUserUseCase {

constructor(private readonly userRepository: UserRepository) {}

async execute(name: string, email: string): Promise<User> {

const existingUser = await this.userRepository.findByEmail(email);

if (existingUser) {

throw new Error(“User with this email already exists.”);

}

const userId = 'some-unique-id';

const newUser = User.create(userId, name, email);

await this.userRepository.save(newUser);

return newUser;

}

}

This use case can be unit‑tested in isolation with a mock repository, which is one of the major gains of the pattern.2

Step 3: Adapters and Controllers

Implement repository adapters in infrastructure (Prisma, TypeORM, direct SQL, etc.) and expose Use Cases via thin controllers in interfaces.

// src/interfaces/userController.ts

import { Request, Response } from 'express';

import { CreateUserUseCase } from '../application/createUserUseCase';

export class UserController {

constructor(private readonly createUserUseCase: CreateUserUseCase) {}

async createUser(req: Request, res: Response): Promise<void> {

try {

const { name, email } = req.body;

const user = await this.createUserUseCase.execute(name, email);

res.status(201).json(user);

} catch (error) {

res.status(400).json({ message: (error as Error).message });

}

}

}

The controller is a thin translation layer; the core application has no knowledge of Express or HTTP specifics.

Weighing the Benefits and Trade‑offs

Clean Architecture is a pragmatic investment. It brings long‑term benefits at the cost of initial complexity and some boilerplate.

Upsides

- Superior testability and faster feedback loops via isolated unit tests.2

- Freedom from framework lock‑in—core business rules remain stable as technologies change.

- Better maintainability and onboarding through explicit structure, reducing long‑term technical debt.3

Trade‑offs

- Higher upfront complexity and learning curve for teams new to the approach.

- Potential for boilerplate if applied dogmatically to small projects.

Choose pragmatically: adopt core principles early without enforcing unnecessary ceremony for tiny prototypes.

Decision Matrix: Is Clean Architecture Right for Your Project?

| Factor | When it helps | When it’s overkill |

|---|---|---|

| Project size | Large, long‑lived systems | Short experiments or throwaway prototypes |

| Team experience | Mixed teams; need for clear boundaries | Small, experienced team shipping quickly |

| Velocity | Slower start, safer long‑term changes | Quick initial delivery required |

| Maintainability | High | Risk of excessive boilerplate |

Common Mistakes and How to Avoid Them

Dogmatism and Over‑engineering

Avoid applying every rule to trivial problems. Use the architecture where it reduces risk, not as a religious requirement.

Leaky Abstractions

Don’t let framework or ORM annotations leak into Entities. Keep DTOs and mappers at the boundaries so the core remains pure.

Anemic Domain Model

Keep behaviour inside entities when logic operates on their state. Avoid turning entities into passive data bags.

Practical Questions

How does Clean Architecture relate to Hexagonal or Onion?

They’re close cousins: Hexagonal emphasizes ports and adapters, Onion uses the concentric metaphor, and Clean Architecture unifies these ideas into a clear, four‑layer model. The Dependency Rule is the shared principle.4

How should I handle database transactions?

Wrap Use Cases with a transactional decorator or use a Unit of Work. Both approaches let infrastructure manage transactions without making the core aware of persistence details.5

Is it suitable for small projects?

If the project is truly short‑lived, the overhead can be unnecessary. If you expect the product to evolve, apply the core separation principles and let the architecture grow as needed.

Three Concise Q&A Sections

Q: What problem does Clean Architecture solve?

A: It protects business rules from technology churn by enforcing an inward dependency flow, making systems more testable and adaptable.

Q: What are the main trade‑offs?

A: Upfront complexity and possible boilerplate versus long‑term maintainability and lower technical debt.3

Q: How do I start pragmatically?

A: Separate domain logic from frameworks first. Define ports (interfaces) for infrastructure and add adapters as demand grows.

AI writes code.You make it last.

In the age of AI acceleration, clean code isn’t just good practice — it’s the difference between systems that scale and codebases that collapse under their own weight.